2 February 1970

Contents: Introductory Note by the American Editor Joseph Kosuth, David Bainbridge, Three from may 23rd, 1969. Frederic Barthelme, Notes on Marat Stephen McKenna, Plans and procédures Michael Baldwin, Dialogue Ian Burn, Moto-spiritale Robert Brown-David Hirons, From an Art & Language Point of View Terry Atkinson, Concerning Interpretation of the Baindridge / Hurell Models Terry Atkinson, Notes on Atkinson’s Concerning Interpretation of the Bainbridge / Hurell Model’s Harold Hurell, Sculptures and Devices Harold Hurell, Conceptual Art: Category & Action Michael Thompson, Notes on Généalogies Mel Ramsden

JOSEPH KOSUTH: INTRODUCTORY NOTE BY THE AMERICAN EDITOR.

Current American art activity can be considered having three areas of endeavour. For discussion purposes I call them: aesthetic, ‘reactive’, and conceptual. Aesthetic or ‘formalist’ art and criticism is directly associated with a group of writers and artists working on the east coast of the United States (with followers in England). It is however, far from limited to these men, and as well is still the general notion of art as held by most of the lay public. That notion is that, as stated by Clement Greenberg: « aesthetic judgements are given and contained in the immediate experience of art. They coincide with it; they are not arrived at afterwards through reflection or thought. Aesthetic judgements are also involuntary: you can no more choose whether or not to like a work of art than you can choose to have sugar taste sweet or lemons sour. »

In terms of art then this work (the painting or the sculpture) is merely the ‘dumb’ subject-matter (or cue) to critical discourse. The artist’s role is not unlike that of the valet’s assistance to his marksman master: pitching into the air of clay plates for targets. This follows in that aesthetics deals with considerations of opinions or perception, and since experience is immediate art becomes merely a human ordered base for perceptual kicks, thus paralleling (and ‘competing’ with) natural sources of visual (and other) experiences. The artist is omitted from the ‘art activity’ in that he is merely the carpenter of the predicate, and does not take part in the conceptual engagement (such as the critic functions in his traditional role) of the ‘construction’ of the art proposition. If aesthetics is concerned with the discussion of perception, and the artist is only engaged in the construction of the stimulant, he is thus — within the concept ‘aesthetics as art’ — not participating in the concept formation. In so far as visual experiences, indeed aesthetic experiences, are capable of existence seperate from art the condition of art in aesthetic or formalist art is exactly that discussion or consideration of concepts as examined in the functioning of a particular predicate in an art proposition. To re-state: the only possible functioning as art aesthetic painting and sculpture is capable of, is the engagement or inquiry around its presentation within an art proposition. Without the discussion it is `experience’ pure and simple. It only becomes ‘art’ when it is brought within the realm of an art context (like any other material used within art).1.

A short discussion of what I call ‘reactive’ art will be necessarily brief and simplistic. For the most part ‘reactive’ art is the scrap-heap of 20th century art ideas — cross-referenced, ‘evolutionary’, pseudo-historical, ‘cult of personality,’ and so-forth; much of which can be easily described as an angst-ridden series of blind actions.2

This can be explained partially via what I refer to as the artist’s ‘how’ and ‘why’ procedure. The ‘why’ refers to art ideas, and the ‘how’ refers to the formal (often material) elements used in the art proposition (or as I call it in my own work ‘the form of presentation’). Many disinterested in and often incapable of conceiving of art ideas (which is to say: their own inquiry into the nature of art) have used notions such as ‘self-expression’ and ‘visual experience’ to give a ‘why’ ambiant to work which is basically ‘how’ inspired.

But work that focuses on the ‘how’ aspect of art is only taking a superficial and necessarily gestural reaction to only one chosen ‘formal’ consequence — out of several possible ones. As well, such a denial (or ignorance) of art’s conceptual (or ‘why’) nature follows always to a primitive or anthropocentric conclusion about artistic priorities.3

The ‘how’ artist is one that relates art to craft, and subsequently considers artistic activity ‘how’ construction. The framework in which he works is an externally provided historical one, which takes only into account the morphological characteristics of preceding artistic activity. This reactionary inputis has left us with a kind of involuted artistic inflation.

Thus the only real difference between the formalists and the ‘reactive’ artists is that the formalists believe that artistic activity consists in closely following the ‘how’ construction tradition; whereas the ‘reactive’ artists believe that artistic activity consists in an ‘open’ interpretation (and subsequent reaction to) not as much the ‘how’ construction of ‘long range’ (or traditional) ‘how’ construction, but the ‘short range’ or directly preceding `how’ construction. But both readings of ‘how’ construction still—in a more or less sophisticated form—are concerned with the morphological characteristics, rather than the functional aspects, of artistic propositions.

Art propositions referred to by journalists as ‘anti-form’, ‘earthworks’, `process art’, etc. comprise greatly what I refer to here as ‘reactive’ art. What this art attempts is to refer to a traditional notion of art while still being ‘avant-garde’. One support is securely placed in the material (sculpture) and/or visual (painting) arena, enough to maintain the historical continuum4 while the other is left to roam about for new ‘moves’ to make and further ‘breakthroughs’ to accomplish. One of the main reasons that such art seeks connections on some level to the traditional morphology of art is the art market. Cash support demands ‘goods’. This always ends in a neutralization of the art proposition’s independence from tradition.

In the final analysis such art propositions become equivicated with either Painting or sculpture. Many artists working outside (deserts, forests, etc.) are now bringing to the gallery and museum super blown-up colour photographs (painting) or bags of grain, piles of earth and even in one instance a whole uprooted tree (sculpture). It muddles the art proposition into invisibility.5

At its most strict and radical extreme the art I call conceptual is such because it is based on an inquiry into the nature of art. Thus, it is not just the activity of constructing art propositions, but a working out, a thinking out, of all the implications of all aspects of the concept ‘art’. Because of the implied duality of perception and conception in earlier art a middle-man (critic) appeared useful. This art both annexes the functions of the critic, and makes a middleman unnecessary. The other system: artist-criticaudience existed because the visual elements of the ‘how’ construction gave art an aspect of entertainment, thus it had an audience. The audience of conceptual art is composed primarily of artists — which is to say that an audience separate from the participants doesn’t exist. In a sense then art becomes as ‘serious’ as science or philosophy, which don’t have ‘audiences’ either. It is interesting or it isn’t, just as one is informed or isn’t. Previously, the artist’s ‘special’ status merely relegated him into being a high priest (or witch doctor) of show business.6

This conceptual art then, is an inquiry by artists that understand that artistic activity is not solely limited to the framing of art propositions, but further, the investigation of the function, meaning, and use of any and all (art) propositions, and their consideration within the concept of the general term ‘art’. And as well, that an artist’s dependence on the critic or writer on art to cultivate the conceptual implications of his art propositions, and argue their explication, is either intellectual irresponsibility or the naivest kind of mysticism.

Fundamental to this idea of art is the understanding of the linguistic nature of all art propositions, be they past or Present, and regardless of the elements used in their construction.7

This concept of American ‘conceptual’ art is, I admit, here defined by my own characterisation, and understandably, is one that is related to my own work of the past few years. Yet it is here at the ‘strict and radical extreme’ where agreement is reached between American and British conceptual artists—at least in the most general aspects of our art investigations—as diverse as the ‘choice of tools’ or methodology or art propositions may be.

There is a considerable amount of art activity between the ‘strict and radical extreme’. and what I call ‘reactive’ art earlier. My contributions by artists working on the American continent will be relatable — whenever possible — to the former, though unfortunately the quantity of such activity make the sole consideration of such contributions impossible.

NOTES

- One begins to understand the popularity among critics of such mindless movements as expressionism, and the general distain toward ‘intellectual’ artists such as Duchamp, Reinhardt, Judd, or Morris.

- Artists in America have a tendency to cloak their investigations in such a way as to enable extra-art justification for their activities. I suspect this has a great deal to do with America’s basic anti- As John Sloan says in « The Gist of Art » (1939) « Artists, in a frontier society like ours, are like cockroaches in kitchens —not wanted, not encouraged, but nevertheless they remain. »

- In recent years artists have realised that the ‘how’ is often purchasable and that purchasability of the ‘how’ (and the subsequent ‘de-personalisation’ of ‘how’ construction) is negatively impersonal only when the `how’ is functioning for a ‘personal touch’ why’ construct.

- And give the art economists and politicians something to ‘invest’ in.

- Unfortunately many of these artists want to reform the system enough to make their ideas acceptable, but not so much as to ruin their chances for ‘success’ in the grand old manner.

- An aspect of this problem is that which was fundamental to our earlier discussion of formalist and ‘reactive’ art. That has to do with the supervisory, even ‘parental’ role critics have taken in the 20th century toward artists; the institutionalised condescention engaged in by museum and gallery personnel; and the peculiar ability artists themselves have to romanticise intellectual bankruptcy and opportunism.

- Without this understanding a ‘conceptual’ form of presentation is little more than a manufactured stylehood, and such art we have with increasing abundance.

DAVID BAINBRIDGE

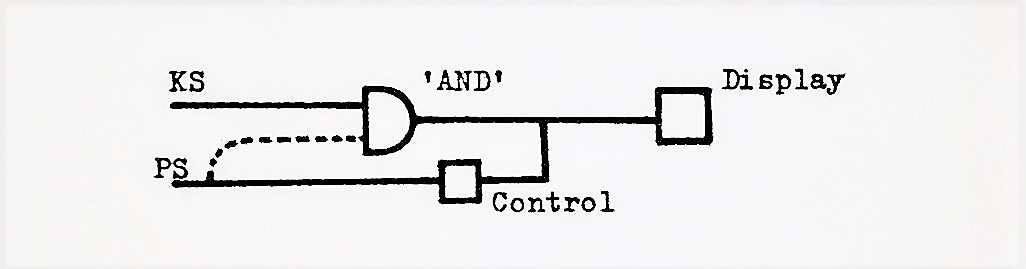

The Sculpture1 is an assembly of switching elements of an electric circuit designed to function in a specific manner2. This assembly possesses two3 inputs and an output, and the performing of a ‘requisite act’ by an operator at an input results in an output. However, such are the characteristics of this assembly and the ‘system’ as a whole that what on one occasion suffices as ‘requisite act’ may not do so on another. Component parts of the assembly are; a capacity proximity switch and a keyswitch which are inputs and a display ‘nidus’5 where output occurs, and a ‘controller’6.

For each of these components is a ‘mode of encounter’ appropriate to their specification. For the key and proximity switches this ‘mode of encounter’ is synonymous with an operator’s performing the ‘requisite act’, the latter merely a behavioural counterpart or demonstration of the former. There being no such requisite act appropriate to the functioning of either controller7 or display this locates them in different and differing sectors of appraisal method.

There is some difficulty insofar as a ‘visual mode’ as the one specifically appropriate to the display is consistently apodeictically basically prior for all components in any empirical demonstration of them. On being placed in a gallery they assume a role of observanda much as other sculpture either currently sharing the same gallery or that previously there in an earlier exhibition. As such, these components, or the assembly as composite are liable for kind of spatial or morphological appraisals as usually attend the ‘visual encounter’. This is the mode specifically appropriate to the display and its specification admits of no other.

With the assembly two further modes are available to an ‘interested’ visitor. These are a ‘perusal’ mode and a ‘scrutiny’ mode which are specifically appropriate to the proximity switch and keyswitch respectively. In order the proximity switch might function according to its specification, i.e. ‘switch’ this visitor is required to ‘perform the requisite act’ of approaching to within a few feet of it thus impinging its capacitive threshold. Similarly with regard to the function of the keyswitch where an act of locomotor dexterity is required.

As a composite assembly, that it might function according to its specification, i.e. produce a display as a consequence of its input conditions being fulfilled, there is a dicontinuity between the requisite act with regard to the components and that act with regard to the whole at certain times, and this is due to the machine’s parameters. There are periods when the act appropriate to the proximity switch is sufficient alone to elicit a display, there are never periods when the act appropriate to the keyswitch is sufficient alone to elicit a display. During these latter periods, our interested visitor must perform both acts ‘simultaneously.’

NOTES

- The three components, proximity switch, keyswitch, and display ‘nidus’, are spatialy displaced ‘grossly’ with regard to each other.8

The controller is located within the display nidus.

On input from the proximity switch (PS above) has the capacity to operate the display provided the controller is ‘passive’ and permits the signal to reach display. When the controller is at state ‘active’ this input signal is routed through the switching element, ‘AND’, where an input signal from the keyswitch (KS above) is also required for this element to produce an output signal to operate display. Since AND can only produce such an output signal when both its inputs supply signals, it can be seen that ‘scrutiny’ alone is never sufficient to elicit a display.

- In a general sense, viewed as in note 2 above as unit mechanism. Rather it possesses one ‘complete’ input and one ‘partial’ input as a result of the necessity to ‘couple’ the keyswitch if a display is to be forthcoming. It requires a different sensibility to the one attempted here in order to take the spatial displacement of these inputs and the idea of their switching function as contingent, as contributing significantly toward describing the artifact.

- Due to the ‘controller’s’ periodically interrupting the proximity switch-display coupling (active state) a visitor’s perusal of this component (proximity switch) will not always elicit a display. This can be regarded as wholly characteristic of the assembly. Whereas, a visitor’s perusal can elicit a display prior to the control state going ‘passive’ due to the action of a second visitor encountering the keyswitch in the specified manner. This state of affairs can only be partially resolved if viewed as a function of the assembly (except, of course, when the keyswitch and proximity switch are encountered by the same person). It is an attribute of the gallery that the constraint on the number of visitors and their locomotor performances is slight.

- Where the « display » takes place’. The display is an acrylic disc which revolves when the input protocol is fulfilled.

- This runs through a fixed bistable cycle.

- Though there may be no ‘act’ in this locomotor’ sense, nonetheless one might speculate on their being a ‘mode’ (of encounter) appropriate to the controller which was ‘theoretical.’